Greater Equity in Global Health Leadership: Gender and Beyond

- Sep 17, 2018

- 4 min read

Reflections from the American Academy of Family Physicians Global Summit

13 September 2018

It’s about time for greater self-reflection on gender equity in the health profession. As guardians of health, physicians and health professionals are committed by oath to promote health equity, but we are not always willing to have the difficult conversations about the deep rooted power structures and relations that drive a culture of inequity to continue to exist in health systems - especially among the health workforce where 70% of the sector is comprised of women.

Health equity and Primary Health Care (PHC), the 40th Anniversary of Alma Ata, was the focus the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) Global Summit. It was clear from the energy at the summit that global health family physicians from all walks of practice and training are keen to achieve health for all. It was truly an honor to deliver a keynote on Gender Equity in Global Health Leadership: Gender and Beyond among fellow primary care physicians. Whilst Women in Global Health is advocating for the 40th PHC Anniversary Draft Declaration to note the critical importance of addressing gender equality in both PHC and UHC, it is this step by AAFP health care providers to engage on gender inequities that demonstrates the growing momentum.

Dialogue on gender equity in medicine and in the health workforce, previously considered a topic reserved for diversity and inclusion themed tracks, is finally getting the center stage spotlight. The New England Journal of Medicine has published two pieces (1, 2) on sexual harassment just this month; earlier this summer, the American Medical Association adopted a new policy to “combat pay gap” in medicine; and this past spring the Lancet launched its special series on #LancetWomen. We are witnessing an unprecedented opportunity for broader reflection on the roles that all members of the health system – especially those from dominant groups - have in advancing gender equity. This introspection goes beyond connecting with the patient, their families and communities, but involves a deeper inspection of the power within the health system—its culture, practices, and policies that promote inequities. It requires that we not only look outwardly at inequities, but at the opportunities to achieve greater equity in our own practice and within our own organizations.

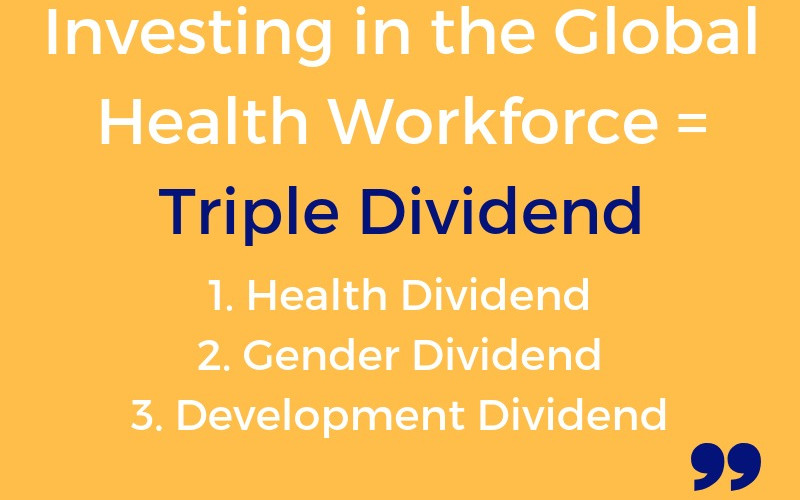

At the AFFP Global Summit, my keynote focused on providing the context: data on the gender gap in global health leadership; focusing on the example of gender and the global health workforce; sharing the current gender deficit and potential triple dividend for health if we achieve gender equality; sharing the latest highlights from the Gender Equity Hub; and opportunities to catalyze change and work together for better global health. While the gender data still continues to have a shock factor – (i.e. the gender gap estimates by the World Economic Forum are that it would take 217 years to close gender gap per modeling calculation in 2017), the attendees were keen to learn about how to address gender inequities - especially in the workplace. A few comments shared (Disclaimer: examples are paraphrased).

Gender Pay Gap

The first comment still remains memorable, as it applies to so many women and highlights why we must move past solutions that focus on fixing women, when gender equality is clearly an institutional matter. A primary care physician, a woman, shared her experience on trying to address the gender pay gap.

“In my community of practice, as women colleagues, we organized ourselves. We determined that there was a gender pay gap in our practice. So we approached our leadership collectively to address the issue, but were denied our request. We were told that we have lower relative value units (RVUs) because we use disability more (only option for maternity leave and carers). What should I do next?”

Answer: Contrary to recommendations that women should negotiate higher salaries - this highlights that the issue is structural and requires institutional changes, including policy shifts in how pay is calculated and how RVUs are measured. Moreover, there is a role for professional associations, unions, and other groups—their collective bargaining power- to address the gender pay gap. The American Medical Association (AMA), recently adopted a plan to combat pay gap in medicine.

Why “Gender Equality” in global health leadership and not “Women”?

This comment highlighted the difference in the global burden of disease among men and women.

“Men are facing higher rates of non-communicable disease and dying at an early age. How do you think gender equality in global health leadership will address the growing burden on men? What will be the impact of more women in global health leadership?”

Answer: Women in Global Health aspires for gender equality in global health leadership, this includes addressing inequities of gender and beyond to promote greater diversity and inclusion in global health leadership, so there are a broader range of perspectives addressing and designing the solutions to our global health challenges.

What tools are there for providers to apply a gender lens to their work?

“As a health provider, I find the social determinants of health framework a useful tool in my practice. Is there a framework similar to the social determinants of health that can be used to address the gender dimensions of health and the health workforce?”

Answer: The social determinants of health include gender as a determinant of health. This same framework can be used to for health promotion, and disease prevention and treatment. However, to go beyond the delivery of care and evaluation of health systems, as well as the broader context, Women in Global Health uses a life course approach and an ecological model to understand the range of gender barriers starting at the individual up to the policy level that impact one’s ability to reach their maximum potential based on gender. We also use the Gender at Work, theory of change, to guide our program and policies, ensuring that they are working toward achieving our vision.

In closing, it is great to see this momentum to achieve greater equity in global health leadership, especially in the health workforce. I applaud the efforts of individuals and organizations that are committed to addressing this issue head on, knowing the uncertainties and complexities involved. The willingness to be gender transformative leaders begins with dialogue and then taking actions to create a gender equality reality for all.

Comments